No one counted me. No one in my college town investigated to determine the source of the bacteria, which almost took my life. No one in any health department noticed my case; I was not part of any counted outbreak. No one cultured me on time.

No one made the proper diagnosis until I was almost dead. Because health care professionals in Alabama were not required to report E. coli O157:H7 a year ago, my disease did not become a statistic in any health department network. No one in the meat industry gave a thought to someone my age. An eighteen-year-old college student. No agency risk considered me when charting those populations that are most vulnerable.

No bureaucrat counts the cost of Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Purpura or TTP, my primary complication, when adding up national medical costs due to E. coli O157:H7. No one recorded that, to date, my medical bills exceed $200,000, approximately a quarter of a million dollars for one freshman at the University of Alabama.

No one counted that my illness kept my parents from working for six weeks as they remained by my bedside in a hospital 250 miles from home. No one in the food industry cared that my family had Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner in a hospital cafeteria. No one counted the six weeks in the spring my mother spent at the University with me as we worked to salvage my 1993 fall semester.

No one tabulated how my medical bills have driven my family into financial ruin. No bureaucrat cares that our $400 per month insurance policy provides no outpatient follow-up care. No one in government thought about the 400+ units of blood and blood products it took to save my life. No one considered how it frightens me to have the blood of a thousand donors coursing through my veins.

No one counted how much energy, and pain, and praying it took to fight my way back from death. These are things that never show up on anyone’s computer model, anyone’s risk assessment, anyone’s “incidence” reports. So you see, no one counted me, Laura Day. No one counted me at all.

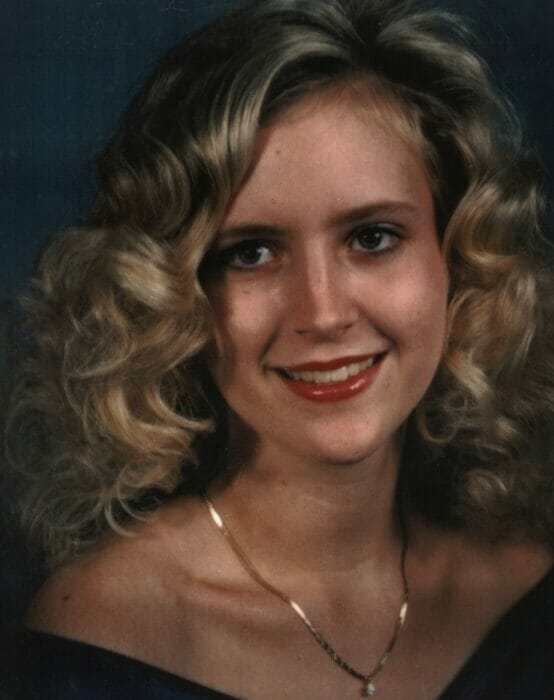

But I sit here before you today with these families to tell you, “I do count. I am not expendable!” My family loves me more than life itself. It devastates them still to think of what happened to me. I had a perfect future ahead of me. In high school, I was on an award-winning dance team, president of the German Honor Club, a contestant in the Miss Ft. Walton Beach High School Pageant, a member of the National Honors Society, Science Honor, and Alpha Tau Sigma, and voted by the students as the smartest girl in the senior class. I graduated fifth out of a class of 453.

In my junior year of high school, I was one of 80 North American students selected for the Daimler-Benz Award of Excellence, receiving a month long all-expense paid trip to Germany. The German ambassador here in Washington, D.C. hosted a luncheon for the 80 recipients and Daimler-Benz executives before we left for Germany. The highlight of the trip for me, personally, was when the chairman of Daimler-Benz International read a quote from my essay as he addressed our group.

When I contracted E. coli O157:H7, I was on full academic scholarship at the University of Alabama, majoring in international finance with a minor in German. Holding offices in the Women’s Honors Program and AIESEC, an international business organization, provided me with many new and exciting challenges. My life was promising and I felt invulnerable. Then something as simple as eating a hamburger changed everything.

November 12, 1993, my brother, Joe who also attends the University, and I went home for the weekend. I began having flu-like symptoms. My mom told me to take some cold medication, and I’d probably feel better by Monday. I was awake all night Sunday. Monday morning I called my brother to take me to the campus clinic where I was kept overnight. Tuesday I was seen by an enterologist at the hospital, who sent me back to the campus clinic to spend another night, in spite of the fact that the stool specimen I took to his office was nothing more than blood. Wednesday morning my condition had worsened. My parents were notified that I was being transferred to a local hospital, and my mother left home immediately to be with me. She expected to find me with a simple virus. She was appalled when she arrived to find much worse. Pallor of the skin, which accompanies E. coli, was already evident. Vomiting, diarrhea, and severe stomach cramps occurred every few minutes. Injections of Demerol every four hours controlled the pain for only a few minutes at a time. I began having unbearable headaches – a condition which would reappear many times throughout my illness. These headaches would sometimes last for days. Many nights my parents took turns all night massaging my temples, my neck, my shoulders and back, trying to make the pain more bearable so that I could rest. Only occasionally were my parents afforded the luxury of an uninterrupted nap on the small cots in my cramped hospital room.

Wednesday night my enterologist informed my mother that I had a bacterial infection which was strongly suspected to be the strain of E. coli associated with the outbreak on the West coast. Thursday night his suspicions remained the same, but no cultures to confirm the diagnosis were done, and the course of treatment had not changed. My mother expressed her fears to him that I was dying and that a diagnosis must be reached so that I could receive proper treatment. A gynecologist, a hematologist, and a urologist were summoned, and additional tests were made. By Friday night the urologist suspected HUS/TTP. HUS or Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome is the most prevalent cause of kidney failure in children. There is a blurred distinction between HUS and TTP. TTP is the adult version and often has the same symptoms but also can include neurological damage. Saturday morning after a telephone consultation with a hematologist at University Hospital in Birmingham, a diagnosis of HUS/TTP was confirmed. Due to my age, I was experiencing symptoms and complications of both.

Saturday morning was the day of the Alabama-Auburn football game. As a happy, healthy college student my plans for that day had certainly never included being transported in an ambulance in heavy traffic at 85mph. During that ride, there were times I could see my mom behind us and I knew how tense and upset she must be, having to follow a speeding ambulance, still unsure of her daughter’s fate.

From the minute we arrived at University Hospital in Birmingham, my parents knew this was where I needed to be. My attending physicians and the entire staff became not only my caretakers, but also our family’s friends. Within two hours of my arrival the first of nineteen plasmapheresis treatments was administered. This treatment is similar to dialysis. Each treatment involved having the plasma removed from my blood and being replaced with 16-20 bags of donors’ plasma. The treatments were horrendous. Sometimes I would have vomiting and nausea throughout these four-hour ordeals. At times I would be very, very cold. At other times there was a painful tingling throughout my body as if an electric current was running through it. Many times I was so adversely affected by the pain, shivers, and nausea that the treatment would be halted until I could bear to continue. However, we could not wait long because my blood in the machine would begin to clot.

The doctors informed my parents on November 20th that very little was known about TTP and its complications. Treatments would be tried one at a time until I responded to one of them – if I responded at all. If we were lucky and I was cured, we would never really know which medication or procedure was responsible.

My body continued to become more swollen from fluid retention. Tuesday night after my 9:00 pm medication I became unresponsive for approximately five minutes then appeared normal again. After my 2:00 am medication I did not respond to my parents or the staff. One side of my mouth was drooping and it was feared that I might have neurological damage. My thoughts were still somewhat clear at this time, and I knew what I wanted to say to my parents. But when I would try to speak, I could only count – 21, 22, 23 – counting faster and faster so that they could not understand many of the numbers. I was combative, suffering from hallucinations, and myoclonic jerking, and had to be restrained. I was rushed for a CT scan, which, amazingly, showed no neurological damage.

My kidneys had completely shut down. Later that morning, as I was being transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU), I stopped breathing. Fortunately, the nurses were able to revive me. My lungs had filled with fluid, and I was placed on a ventilator to help me breathe. Weeks of respiratory therapy followed.

Thanksgiving Day, as other families celebrated the holiday together, the nurses in MICU were kind enough to break all of the rules and allow my parents, my brother, and seven other family members extended visiting privileges even though I was comatose and unaware they were there. My grandparents began their 200-mile journey home Thanksgiving evening believing they had seen me for the last time.

On November 26th, I regained consciousness after being non-responsive for three days. My parents still have the notes I wrote, in kindergarten-like penmanship after I regained consciousness. The first question I wrote, a typically-teenaged one, was where are my rings? My class ring and birthstone had been removed because of the severe swelling. As my kidneys failed, I gained 30 pounds in less than a week. I was unaware that I was on a respirator and my second question was, will I ever be able to speak again? My throat was so sore that I could not speak above a whisper for days after the ventilator tube was removed.

I left the MICU after four days and my health actually improved for a few days. Just when we had renewed hope that I was getting well, all of my blood functions started crashing again. The platelets in my blood were still being destroyed by the infection. A myriad of complications and procedures followed, including more plasmapheresis and chemotherapy. My platelets were being destroyed and those that remained were not healthy.

My platelet count was so low that the slightest touch to my skin created a new bruise. Petechiae and ecchymoses, two separate forms of bleeding under the skin, caused purple blotches all over my body. I also had deep purple stretch marks from the rapid weight gain.

As my kidney functions improved, the fluid retention lessened, and I began to look more like myself. Then came the anabolic steroids. The steroids caused more puffiness and brought steroid acne to a formerly flawless complexion. I also began to lose my hair as a result of chemotherapy, which I had begun when I was in the MICU.

I then underwent a very painful bone marrow scan, which provided no new information, nor did two exploratory abdominal ultrasounds. For weeks as I would try to read, I was painfully aware that my thought process had drastically slowed. I began to wonder if this condition would last, and if it did what my future would be like. My blood pressure was dangerously high, accompanied by frequent nosebleeds. My headaches were especially bad during this time. Whole blood and gamma globulin were administered on days when I was not given plasma exchange. Still I did not improved. Nothing the doctors had tried was working.

As a last resort, my team of doctors decided to remove my spleen in an attempt to save my life. We would not have been as optimistic about this procedure had we known that three days before I arrived at University Hospital a 26-year-old female had died from complications of TTP. The splenectomy made no difference in her case.

Luckily, after the splenectomy my platelet count improved dramatically. I spent Christmas Day sore, scarred, bruised, weak, and losing hair, but relieved that I would be able to leave the hospital in a few days. I was one of the fortunate few TTP survivors.

On December 27th we tearfully said goodbye to the staff and began our five-hour drive home. I continued to suffer from anemia, high blood pressure, kidney problems, and an uncomfortable strange tingling in my fingertips for months. I still have stretch marks from the severe weight gain and a scar on my stomach from the splenectomy. My hair is still in the process of growing back. I have worn a baseball cap for the past ten moths and have just now been able to go without one. The removal of my spleen has left my immune system compromised. Now, as evidenced by my September 1994 hospitalization, a simple virus often requires special treatment. I am much more susceptible to colds, viruses, and the flu. Neither my doctors no I know what my future will hold. Will I have kidney problems, high blood pressure, problems with my reproductive system? No one knows.

Many of you probably have children close to my age. When they go away to college, you worry about the choices they will make: choosing to drink, smoke, have sex, do drugs. Few of you will worry about your kids choosing to go out for a burger. Your children will have no choice with E. coli O157:H7. It will choose them. You, the United States Congress has the choice to either protect the American people, or turn your back on them and bow once again to the wealthy meat industry’s selfish demands. The meat industry will tell you they want a system to protect people, but it has not, and will not, happen unless Congress takes action.

I am back in school and have resumed a full academic and social schedule. However, I will be watching very carefully what this Congress does with meat inspection reform this year. America is going to be watching very carefully, because this decision affects families on the most basic level of health and safety. Safe food should be given in any civilized society, at least any society that I want to be a member of. This Congress has a responsibility to do the right thing for the citizens it now has an opportunity to stop this kind of senseless human suffering.

No one counted me. But I will be counting; I will be counting very carefully what Congress does about contaminated meat in America and the Family Food Protection Act of 1995. E. coli O157:H7 tried to take my future from me and failed. The many who have not survived their battle with E. coli are represented by my voice and my vote to bring reform and I, along with every family affected, will be counting.

~ Testimony of Laura