“My tummy hurts. My tummy hurts. My tummy hurts.” My three-year-old daughter repeated this over and over again. Until that Tuesday evening, Anna had never complained about pain of any sort. In fact, when she fell down, she would leap up and say, “I’m OK,” and run off. Indeed, Anna was one, healthy, big kid for her age at 35 pounds. Though we eat out frequently, we have always tightly restricted her intake of sweets and pushed a lot of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and milk products like yogurt and cheese. She eats at fast food restaurants at most twice a year.

My husband and I had been on a rare Mommy-Daddy-only vacation when Anna fell sick. “I took her to the pediatrician’s yesterday,” Grandma said, though it was clear that she was worried. “He said it was probably flu, and she should be better by tomorrow.” By the time we returned from vacation, Anna had had chronic diarrhea with stomach cramps for four days, day and night. That night, I learned that the stomach cramps would even awaken her from sleep. Her diarrhea, at that point mostly fluid, was an odd, orangeish color. “By the way, I bought some of that Odwalla apple juice at the grocery store. She really loves it! We went through a whole jug of it and then I went back to the store to get more,” my mother added. I frowned. Apple juice is notoriously low in nutrition. We usually fed Anna strawberry/banana or sent her to nursery school with Odwalla carrot juice in her lunch box, but Grandmas have privileges that parents often don’t.

We scheduled a second appointment with the pediatrician the next day, and he was concerned it was food poisoning, either Shigella, Campylobacter, or Salmonella. It has recently become known that antibiotics given to kill off the first two can drive Salmonella into the gallbladder, so the doctor wanted to be sure of the infectious agent. Through the stethoscope, the rumbling in her tummy was loud and clear. He and I agreed that her stool might have blood in it, but neither of us was sure. We gave the lab a stool sample, which would take at least two days to culture. When Anna wasn’t running to the bathroom, she was lying in my arms, at times only whispering, “My tummy hurts. My tummy hurts.” Because she had to get up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, I slept in her room, awakening every two hours.

By Thursday, she had had diarrhea for six days straight and hadn’t eaten in four. She was going through panties so often that I put her into pull-ups at great offense to her ego. That afternoon, when there was still no sign of improvement, I took her to the doctor’s office for an IV. I thought I was being overly concerned; she’d never been this sick, and I was overreacting. My mother and I spoke frequently about where she might have contracted it. We reviewed what she had eaten. We noted that she had been to a petting zoo. I asked at her nursery school whether any other children had fallen similarly ill. There was no source. Because Anna was only drinking water, the doctor asked us to begin pushing fluids such as apple juice. I bought some more Odwalla apple juice and lots of Gatorade, but Anna would only drink a couple of sips at a time.

On Friday, after seeing her again, and after the results of her stool culture all came back negative, the doctor prepared me for the weekend. I should bring her in for a second IV if she didn’t drink a certain amount every hour. I should also bring her in if she developed a fever or if she didn’t pee more than twice in 24 hours. That night, Anna showed some brief improvement. As we ate dinner, she asked for some pasta of her own and ate a few pieces without anything on them.

Early Saturday morning, I thought we were making progress. Anna was drinking some fluids, and she hadn’t had diarrhea or peed since late on Friday. By the middle of the afternoon though, she had fallen behind in fluids and still had not peed. I spoke to the doctor on call. My husband thought I was worrying too much; she just needed to be pushed harder to drink fluids. We went to the emergency room to get an IV, and there, she vomited up all of the fluids she had consumed in the last five hours. The pediatrician on call took a sample of her blood before starting the IV, and fairly quickly thereafter, Anna had to go pee again.

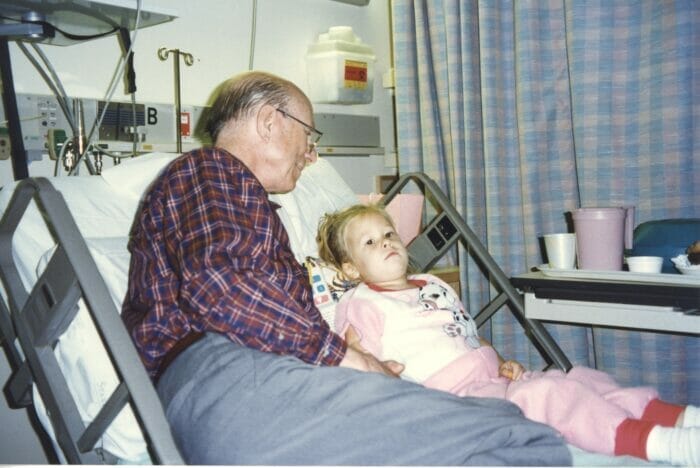

“We’re admitting her,” the pediatrician on call announced. She went on to describe Anna’s blood counts were all slightly abnormal. Her creatinine, a measure of kidney function was not good. A month before, my aunt had died of complications resulting from chronic kidney disease. “We’re familiar with creatinine,” I said, explaining about my aunt. “That’s the one we worry about.” Admitting Anna also seemed like an overreaction, but she was clearly dehydrated. Better to be watched carefully rather than kicked out too soon. I nominated myself to stay at the hospital. That night, the electronic thermometers were not working, and they took Anna’s temperature rectally. By the time they came a third time, she yelled, “I don’t want them to put that stick in my bottom!” They took blood every four hours. I think the only way Anna managed to sleep was through exhaustion.

By 1:00a.m., I had barely slept. The bed I was given had loud squeaking springs. At one point, it almost collapsed on me, and I was trying to not wake Anna up. The nurse put through a call from the pediatrician. “We’ve identified Anna’s illness,” she said. “We think she has HUS.” I tried to follow what she was saying, but it all seemed like jargon. HUS was the leading cause of acute renal (kidney) failure in children. It crops up most often in the summer and fall. Children can get it from fast food places and swimming in lakes, neither of which Anna had visited. When they see clusters of cases, the doctors presume it is an outbreak of E. coli O157. Children can recover in 2 to 3 weeks. They were going to transfer her to Stanford Children’s Hospital, where the disease would be treated aggressively. She went on to talk about Anna’s increasing anemia. “Because you mentioned the creatinine and it’s increasing, I thought about this disease in particular. That’s why we checked under the microscope. When we found broken red blood cells, I suspected HUS, so I called the renal specialist at the Children’s Hospital, and he agrees.” The doctor closed with, “I’m very sorry that I have to tell you this. I told the nurse, ‘That poor mother…’ getting news like this in the middle of the night.”

I couldn’t understand the significance. Were Anna’s kidneys failing? I tried to call Scott, my husband, but our phones at home shut down at night. It was a long, lonely night. How would they treat this? What did it mean? Because I had received the early morning call about my aunt’s death, I knew the phones would turn back on at 6:00a.m. and called Scott promptly. After repeating as much as I could remember, I asked, “Please get on the Internet. Look for “Hemolytic uremic syndrome” and “E. coli O157. ” Scott came about an hour later.

As I poured over the materials, tears welled up in my eyes. At the Synsorb Biotech, Inc. site, it read: “Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) is a disease that affects the kidneys and other organs. It poses a threat…as one of the leading causes of both acute and chronic kidney failure… The most common symptoms of E. coli O157:H7 Gastroenteritis or Hamburger Disease include: Diarrhea (often with blood in the stools), Vomiting, Abdominal Cramps…E. coli O157:H7 bacteria infect the intestine of cattle and less frequently the intestines of other animals. Typically carried in the feces, it can contaminate the meat during and after slaughtering. These bacteria are associated mainly with consumption of undercooked ground beef, unpasteurized milk and cheese, and contaminated water sources… If HUS develops, children spend an average of 2 weeks in hospital mainly to care for kidney problems of varying severity. Depending on the severity of the illness, a large majority will require some form of blood transfusion and approximately 50% will need temporary kidney dialysis. Modern medical care has allowed approximately 97% of the children to survive the illness; however, long-term follow-up is very important.”

The Lois Joy Galler Foundation was more dour, and I began to sob: Only 1 in 10 children develop HUS following an E. coli infection. “HUS is a dramatic, explosive illness that most commonly develops within 2 to 4 days after a bout of gastroenteritis that is accompanied by bloody diarrhea. Children are hospitalized with obvious irritability, fatigue, pallor and a noticeable decrease in urine production. Some severely affected children may have life-threatening gastrointestinal problems. Neurological dysfunction including lethargy, seizures, cerebral infarction, blindness and coma can be present at disease onset or develop during the course of the illness. Profound gastrointestinal or neurological disease are markers for more severe cases of HUS and may be harbingers of a poor prognosis.”

“Nearly 5-10% of children with HUS die during the acute phase of the disease as a consequence of complete renal failure or multiple organ complications. A small majority of children with HUS experience a complete recovery with full restoration of kidney function and almost no risk of the disease recurring. However, 10-30% of the children who survive have permanent kidney damage and many of these children will have progressive loss of kidney function over the next 5 to 10 years.”

I went into the bathroom in Anna’s room to take a shower. With the water falling all around me, I began to sob uncontrollably. What had happened to my little girl? Why was this happening to us? What lay ahead of us? How bad was it going to get? Would Anna ever come home with us? What if she were left blind or brain damaged?

As we waited for the ambulance to come, we watched a Sesame Street video about Big Bird’s trip to the hospital, which almost comically, word-for-word mimicked much of the situation as Anna was seeing it. We talked up the ambulance trip between the two hospitals to Anna. She wanted to walk to the ambulance rather than ride on a gurney, and so, with her IV bag attached, four ambulance people and a nurse, we went to the ambulance outside.

At Stanford, we went to a special wing. On the entrance doors to the wing, there were large signs indicating that this was the Immunologically Suppressant Ward; here, children were awaiting transplants. We walked past some rooms, and on the outside of two, I saw photos of the children as they had been before they got sick. We were put in a special room with air filtered as for transplant cases. There was an anteroom for observation; it was the biggest single hospital room I had ever seen.

Late in the day, Dr. Mak, the pediatric-nephrologist came to visit. He indicated that they had not found E. coli in Anna’s stool back at the original hospital, but in 50% of all cases, they never did find it; sometimes, HUS can be caused by other agents. E. coli, he believed, was a reportable disease in the State of California, but HUS was not, and he didn’t believe Anna could be part of an epidemic because Stanford had not seen any number of cases at a rate different than they usually did.

In HUS, the infectious agent spews toxins into the blood stream. Because it is not always known whether it is viral or bacterial, little is done to the original agent after the onset of HUS, but the symptoms must be monitored carefully to minimize damage. As I best understand this, they believe that toxins cause platelets to clump together and stick to the sides of the blood vessels. They also become “sharp,” perhaps like a net made up of knives, and they therefore cause the red blood cells to become broken. Most of the damage appears to occur in capillaries where the passageways are “small” and the RBCs probably cannot “get by” without brushing up against these. The kidneys, because they filter blood on such a detailed level, are a particularly sensitive organ to this type of damage but the damage happens to all organs.

As a result, the symptoms resulting are anemia (loss of red blood cells), loss of platelets, and micro-damage to blood cells. As the kidneys suffer damage and renal failure begins, the patient takes on fluid, eventually no longer peeing on their own. The fluid increases the chances of high blood pressure. Electrolytes become imbalanced, and if potassium goes too high, it can damage the heart. Examples of extreme symptoms are complete kidney failure, strokes causing brain damage, coma, and blindness. However, about 98% of Dr. Mak’s patients had gone home healthy.

The doctor described Anna’s case as being “moderate.” He indicated that Anna would get worse before she would get better, and they needed to watch her carefully. Indeed, she was up and acting like she was getting better already–all this transplant ward stuff was really looking like throwing a grenade when a water balloon would do. As for transfusions, which were likely given where her blood counts were going, we, her parents, were not advised to donate our blood. Because we were the best donors of kidneys should she ever need a kidney, they didn’t want her immune system to develop antibodies to our blood which would down-the-line interfere with her ability to accept a kidney from us.

Anna did very well on Sunday and Monday… she was active and laughing despite the fact that her blood indicators were showing decreasing red blood cells, decreasing platelets and increasing wastes building up in her blood. She was learning to draw with her left hand because the IV site on her right arm inhibited her use of her right hand. Good signs were that she was continuing to pee and had normal blood pressure. On Monday night, they endeavored to give her a transfusion, but she broke out in hives, so they had to back off. They could not determine the cause of the allergic reaction.

That day, Scott read on the Web that “road-side” apple juice had been the source of one E. coli outbreak. We wondered about the juice because it had featured so prominently in my mother’s description of Anna’s week at her house.

By Tuesday, Anna became increasingly irritable. Her normally rose-red lips lost color, and the rest of her color became quite ashen, as if dead. She became puffy, especially in her hands and feet where her arches disappeared, and they had to cut off the bracelets they had strapped on her within the last two days because they became too tight. She was on IVs until it was determined that she was “taking on” fluids, at which point she was placed on a fluid restricted diet. She would beg us for water, but we could give her only a sip every hour. Her lips became dried and bloody.

Tuesday afternoon, a friend stopped by and mentioned that she had heard they were recalling Odwalla apple juice in the State of Washington for having caused an E. coli outbreak there. Somewhere between 10 and 13 people had been affected. Scott called Odwalla, finally speaking with a founder about Anna’s situation. As I began to think about it, even though Stanford seemed to have thought the other lab had tested for E. coli, I didn’t remember anyone actually ordering such a test. As far as I remembered, we had only tested for Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Shigella. Now, Anna hadn’t had a stool in over four days. When questioned, the Stanford nursing staff reported back that there was actually neither a positive nor a negative on the stool culture for E. coli. I called Anna’s pediatrician and left a message.

Scott also initiated a call with the Santa Clara County Department of Health. They were very interested and said that HUS had just recently become a reportable disease in California, though they had no other examples found in Santa Clara County. Ironically, Stanford is just the other side of the border for San Mateo County. My mother had purchased the apple juice in San Mateo County, and shortly thereafter, cases were reported in San Mateo County.

They began a second transfusion on Tuesday afternoon. To reduce the likelihood of an allergic reaction, they gave her Benadryl and Tylenol and “washed down” the blood to be transfused. Anna’s eyes became glassy, and she stared into space when she wasn’t sleeping. As it went on, her color returned, but her numbers did not improve the way they expected. In fact, her platelet counts plummeted. Her BUN, a second measurement of wastes, rose above 100–in some patients, a sign of impending dialysis. They were constantly measuring the amount she peed, trying to determine whether her kidneys were keeping up with the fluid.

We were exhausted, living on at most four hours of sleep per night. Any time, day or night, that a transfusion or IV line didn’t flow correctly, an alarm that sounded like a doorbell would go off, repeating itself until we could get a nurse to change it. Likewise, if Anna bent her right index finger, her heart rate monitor would sound off. They moved us to another, smaller room in the ward, and I asked our friends not to visit because the grandparents, Scott, and I were now snapping at each other.

Word came back from Anna’s primary pediatrician–they had never tested for E. coli. He was upset. “It’s standard practice to look for E. coli as part of these tests, but the lab decided her stool wasn’t ‘bloody enough.’ ‘Not bloody enough’ — sounds real scientific, doesn’t it? We’ve got to change the standard practice.” Had E. coli been found early on, it was possible it could have been treated with antibiotics. Wednesday evening, the local news stations covered another child who had fallen ill and was at Oakland Children’s Hospital. She was already on dialysis. Scott and I agreed that our objective had to be to help other parents quickly identify this illness; we gave the media department a statement about Anna’s condition.

Thursday, though Anna was looking better and some of her blood signs were improving, her platelet and red blood cell counts were still low. Because her kidney output was fine, she was taken off of the restricted fluids diet. Her normal blood pressure made everyone optimistic, but they wanted to give her a third transfusion. We mistakenly believed they could give us blood from the same source as the original transfusion, and we caused a stir when we insisted on speaking to the doctor about getting blood from the same source. It wasn’t possible, and we were confused. And tired.

Because Anna had still not had a stool, the doctors offered to do a rectal swab to see if they could find the E. coli. For them, the E. coli search must have seemed like a boondoggle. They were not seeing more cases at Stanford which would suggest an epidemic, and knowing that it was E. coli would not at that point have changed the treatment. But we wanted to know the source. Just when we thought we might have to do the swab, Anna passed her first stool in six days. It was rushed to the lab to be cultured.

On Friday, we received the great news for which we had prayed. Anna’s creatinine had gone down, and her platelets had shot back up. Her red blood cell counts were creeping back up as well. They were thinking she might go home the next day! An official from the Santa Clara County came to ask us the questions we had already asked ourselves. Had she been swimming in any bodies of water? Had she been to any fast food restaurants? Had she eaten any ground meat or unpasteurized cheeses? They took our empty and half-full Odwalla juice bottles. One from Grandma’s house had the stamp: October 24, 2FN on it. The other jug or jugs were already gone to recycling. We also were visited by one of the founders of the Odwalla company, who had left an emotional message on our answering machine the day before. Remarkably, she arrived just as things were finally looking up; she was as upset and apologetic as one can be without admitting fault. We believed that the “friend” who came with her was probably a lawyer.

Anna returned home from the Stanford Children’s Hospital on Saturday, November 2, around 1:00p.m. on Saturday. Her condition was not yet normal–she was anemic with a low platelet count–but the doctors have never seen a case of HUS relapse after the appropriate indicators turn the corner, so they felt confident in discharging her.

The doctors encouraged us to keep her home the first week in order to avoid any “accidents” which might result in bruising or cuts that required more platelets. Because this disease is relatively new, her long term prognosis is unknown. Her first blood check showed that her platelets had risen into a normal range. Three weeks after discharge she was still excreting blood cells in her urine and was still anemic. They will check her again in mid-December and continue to check up on her every year until adulthood. Possible long-term complications include kidney failure over time, permanent neurologic injury, and/or high blood pressure. E. coli O157:H7 was only recognized as the source of illness in 1982 and as a cause of HUS in 1985. Therefore, there is relatively little long-term data.

Anna’s stool culture results finally came back positive for O157:H7 more than a month after they were first taken to the lab. The State of Washington has found E. coli contamination in Odwalla apple juice with a lot number 2FO and the same expiration date as the bottle in Grandma’s refrigerator. However, they could not find E. coli in Grandma’s last jug of apple juice. When questioned about why the State of California’s response was relatively slow compared to the State of Washington, Dr. Jim Stratton, State Health Officer, indicated that there are three key features of Washington:

1. Washington has had multiple outbreaks and is therefore prepared to move quickly.

2. There is a single pediatric hospital in the Seattle/King County area; therefore, all cases are brought into a single point of communication, so an epidemic becomes obvious.

3. All diarrheal stools, bloody or not, are tested for E. coli. California chooses to test only bloody stools, thus choosing to miss cases. This lack of data, coupled with a lack of centralized reporting to a single source means that the U.S. does not have a firm grip on the increasing spread of this organism, nor can they tell you the likelihood of your child coming into contact with it.

What Needs To Change

The present notification and investigation systems available in most of the United States and the State of California are inadequate for detecting and preventing the spread of food poisonings, which can be deadly to children and adversely affect pregnant women. The nature of the United States in the 1990’s is that fresh produce and goods and ground-meat products, which can be contaminated with E. coli, can be distributed over many states and cause widely distributed epidemics that are no longer simple, isolated incidents such as local, roadside apple cider. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a responsibility to make HUS a reportable disease in order to assist in the rapid gathering of information and preventing further spread of disease.

Throughout California, each county must begin immediately notifying neighboring counties of cases of suspected E. coli poisoning and HUS rather than waiting for the State Department of Health to begin its bureaucratic process. The nature of food poisoning is that by the time the symptoms are cultured and obvious, the initial food and thus evidence has been thrown out; yet, food still harboring infectious agents sits waiting on shelves for unsuspecting consumers. In the time that it takes bureaucracies to move forward, more children can be afflicted. I believe that the Seattle-King County Department of Public Health in the state of Washington has done more in this investigative area than other counties because they have been hit three times now with outbreaks of E. coli: once with the Jack-in-the-Box case in 1993, once with a salami case in 1994, and now with Odwalla. Other county health departments should follow King County’s example in the speed with which it acted to determine the cause of the infection and prevent its spread.

Blood labs MUST routinely scan for E. coli poisoning whenever any food poisoning such as Salmonella, Shigella, or Campylobacteris suspected, regardless of whether the stool appears bloody. If the course of treatment for the initial patient is not changed, at the very least, other cases may be prevented. Tests must be developed that rapidly determine infection from E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella. The present stool culture mechanism is ridiculously long and hopelessly inadequate for quickly determining and acting upon a deadly disease.

Lastly, parents must be constantly vigilant for this type of disease. The symptoms of E. coli poisoning may be similar to the flu, but they are not identical in all cases. In our daughter’s case, the diarrhea did not appear particularly bloody. There was no fever, and there was no vomiting. However, there were constant, painful stomach cramps that awakened her every two hours throughout the night. Though she was toilet trained, she could rarely get to the bathroom in time.

As for Odwalla, I believe that the management team has an opportunity to lead the natural-food industry in researching new tests that quickly and accurately determine the contamination levels of fresh juices. Should the natural-food industry find itself unable to regulate contamination out of its products, I believe that all apple juice should carry a blatant warning: “WARNING: unpasteurized apple juice has been identified as a potential source of E. coli O157:H7 infections which can make you sick and are deadly to small children.” Likewise, the stores that carry organic produce should be required to post signs that say: “WARNING: this store sells produce of undetermined contamination levels. Food sold here may be contaminated with E. coli O157:H7, which is known to be deadly to small children.” We don’t feed alcoholic beverages to small children; why would we give them juices that might kill them?